Systemic rheumatic diseases (RDs) commonly arise during a woman’s reproductive years and may have implications for family planning and pregnancy. Among the RDs, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) are classically associated with an increased risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes (APOs), including miscarriage, foetal loss, preeclampsia, intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) and preterm delivery.1–4 Although SLE pregnancy outcomes have improved over time, maternal mortality remains higher in women with SLE than in the general population.1,2,5 Having SLE and/or APS poses a risk of maternal morbidity related to exacerbation of the underlying disease, organ damage, and thrombotic, haematologic and infectious complications.2,4–6

Studies suggest that women with inflammatory arthritis face unique health risks to varying degrees, depending on the diagnosis and disease status of the individual when she becomes pregnant. Disease activity may improve during pregnancy for some women with rheumatoid arthritis (RA), psoriatic arthritis (PsA), and spondyloarthritis (SpA), but inflammatory arthritis may also be associated with increased risk of APOs, including preterm and caesarean delivery (C-section).7–11 Research that informs family planning and pregnancy considerations in women with other RDs is more limited. In general, achieving disease quiescence using pregnancy-compatible medications prior to conception improves maternal and foetal outcomes regardless of the underlying RD. As a corollary, for women with RD who have active disease, use teratogenic medications or have severe end-organ damage, the use of safe and effective contraception to prevent pregnancy is crucial.

We reviewed English-language studies addressing family planning, fertility, pregnancy risks and management, and postpartum considerations, as each topic pertains to people with underlying RD in general and with reference to specific RDs (i.e. SLE, APS, Undifferentiated Connective Tissue Disease [UCTD], RA, PsA, SpA, idiopathic inflammatory myopathy [IIM] and systemic vasculitis). We excluded case reports and small case series. We will discuss the latest evidence and relevant guidelines to inform the evaluation and management of women with RD before, during and after pregnancy, and we will highlight points of uncertainty or disagreement where further research is needed.

Family planning

The Role of the Rheumatologist

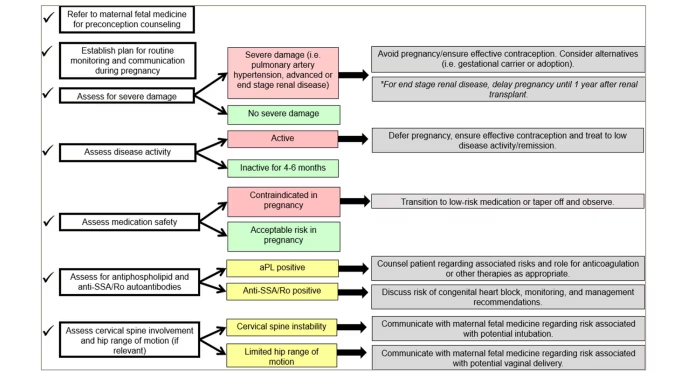

Women with RD face unique challenges related to their reproductive health. Rheumatologists, as specialists familiar with the complexities of chronic autoimmune diseases and their unpredictable and evolving trajectories, play a central role in the management of reproductive health issues. Figure 1 delineates the basic steps that rheumatologists can take when assessing a patient contemplating pregnancy.

Figure 1: Checklist of items for rheumatologists to consider when managing a patient who is planning for pregnancy

aPL = antiphospholipid antibodies; SSA/Ro = Sjögren’s syndrome A.

Qualitative studies exploring the perspectives of patients with RD on reproductive health have found that patients look to their rheumatologists to initiate discussions about reproductive health concerns and to communicate directly with obstetrician/gynaecologists (OB/GYNs).12 Women with RD who are not actively pursuing pregnancy often have questions and concerns about contraception and the impact of their disease and medications on future fertility.13 In addition to concerns about disease- and medication-related pregnancy risk, women with RD also express concerns about the heritability of their disease and the potential impact of their disease on their ability to care for themselves and their offspring.13 It is likely that these factors contribute to the observed decreased family size in women with RD compared with women without these conditions.14,15 The 2020 American College of Rheumatology (ACR) reproductive health guideline recommends that rheumatologists treating women with RD of reproductive age discuss contraception and pregnancy plans at an early visit, periodically thereafter and whenever initiating teratogenic medications.16 The ACR guideline mentions One Key Question® – a simple pregnancy intention screening question – as an option for rheumatologists to use in clinical practice.16,17 One 6-month quality improvement study demonstrated the feasibility of implementing One Key Question in an academic rheumatology setting; although uptake was low, the use of any pregnancy intention screening tool was associated with increased contraceptive documentation and OB/GYN referrals.18 Furthermore, the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) recommendations highlight the importance of counselling women with SLE and/or APS about fertility issues and pregnancy prevention in high-risk scenarios.19 Guidelines and prior studies highlight the need for rheumatologists to collaborate with OB/GYNs in the delivery of reproductive healthcare for patients with RD.12,16,20,21

Contraception and Pregnancy Termination

The use of safe and effective contraception is critical for women with RD who do not desire pregnancy or for whom pregnancy would not be medically advisable due to treatment with teratogenic medications, disease activity and/or severe end-organ damage. However, women with RD of reproductive age often are not prescribed effective contraception, even when treated with teratogenic medications.22–24 While rheumatologists do feel responsible for contraceptive counselling,20 they may be uncomfortable with this area and may not provide adequate counselling.12,18,20,23,25 Young women with RD often turn to OB/GYNs for information and support.13 A 2021 US electronic health record-based study found documentation of contraceptive counselling to be poorly standardized and inadequate.26

The main advantages and disadvantages of various contraceptive methods for patients with RD are summarized in Table 1. There are no contraindications to the use of highly effective long-acting reversible contraceptives, including intrauterine devices and subdermal progestin implants; with typical use, fewer than 1% of women will become pregnant per year.16 The next tier in efficacy includes combined oestrogen-progestin contraceptives, progestin-only pills and depot-medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA) injections; with typical use, between 5% and 10% of women will become pregnant per year.16 Oestrogen-containing contraceptive methods increase thrombotic risk and should be avoided in patients with antiphospholipid antibody (aPL) positivity (defined based on established classification criteria).16,27–30 While the results of studies focused on thrombotic risk with progestin-only pills and intrauterine devices are reassuring, limited data suggest an increased thrombotic risk with DMPA injections in the general population;31–34 DMPA injections should be avoided in patients with aPL positivity.16 There has long been concern for SLE exacerbation due to oestrogen exposure. The landmark 2005 Safety of Estrogens in Lupus Erythematosus National Assessment (OC-SELENA) study, a randomized placebo-controlled trial evaluating SLE flare in patients taking combined oestrogen-progestin contraception, did not find an increased risk in the treatment arm.35 However, those with highly active disease, aPL positivity and history of prior thrombosis were excluded. In these high-risk patients, the recommendation is to avoid oestrogen-containing contraceptive methods.16

Table 1: Advantages and disadvantages of available contraceptive methods for patients with systemic rheumatic disease

|

Efficacy |

Method |

Advantages |

Disadvantages |

|

Highly effective* |

IUD |

|

|

|

Subdermal implant |

|

|

|

|

Effective† |

Combined oestrogen–progestin oral contraceptive |

|

|

|

Progestin-only pill |

|

|

|

|

DMPA injection |

|

|

|

|

Vaginal ring |

|

|

|

|

Patch |

|

|

|

|

Least effective‡ |

Barrier methods |

|

|

*<1% of women experience unintended pregnancy within 1 year of typical use.

†5–10% of women experience unintended pregnancy within 1 year of typical use.

‡15–20% of women experience unintended pregnancy within 1 year of typical use.

aPL = antiphospholipid antibody;APS = antiphospholipid syndrome;DMPA = depot-medroxyprogesterone acetate;IUD = intrauterine device;RD = rheumatic disease;SLE = systemic lupus erythematosus.

There is disagreement regarding the safety of progestin-only contraceptives for women with SLE and aPL positivity. The ACR reproductive health guideline recommends their use in this context, but Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines endorsed by the Society for Maternal–Fetal Medicine (SMFM) do not.16,36,37 While robust safety data in these patients are lacking, there is no evidence of increased thrombosis or disease flare risk due to progestin-only contraception; risks must be weighed against those associated with unintended pregnancy, which are significant. There are no contraindications to using less effective contraceptive methods, including barrier methods that offer protection against sexually transmitted infections, fertility awareness-based methods and spermicides.37 However, these are generally considered inadequate as a sole method of pregnancy prevention; with typical use, up to 20% of women using these methods will become pregnant per year.37 Rheumatologists should routinely discuss emergency contraception, including over-the-counter levonorgestrel, as a safe backup method for all patients with RD who are at risk of unintended pregnancy.16

Recent legislation in the United States that limits patients’ access to termination, such as in the case of an unintended and/or high–risk pregnancy, further underscores the importance of effective contraception use.38 To date, there is very little research regarding pregnancy termination in the context of RD. Studies have shown that the rate of induced abortion among women with RA and SLE of reproductive age may be the same or lower than the rate reported in the general population, even among those taking teratogenic medications.39–41 One study, in which one in four women with SLE or APS reported a prior termination, found that the procedure was recommended due to foetal or maternal morbidity in 2% of incident pregnancies; patients reported no disease flares or significant complications due to pregnancy termination.41

Concerns about Fertility and Conception

Whether people with RD are at an increased risk of infertility compared with healthy individuals is the subject of on–going research. Some cases of primary ovarian insufficiency (POI) and infertility in women with RD may be driven by autoimmunity.42,43 Small studies have identified anti-oocyte antibodies in the serum of patients with SLE and DM,44–46 but the aetiologic significance of these findings has not been firmly established. Several studies have found a correlation between SLE and decreased ovarian reserve, independent of cyclophosphamide (CYC) use, but others have not;47–52 a published review devoted to this topic presents more detailed information on individual studies.53 Several indirect risk factors contribute to infertility and delayed conception in women with SLE, including medication use.54 Paediatric SLE may be associated with menstrual irregularity and pituitary hormone abnormalities.55,56

Some studies show that aPLs (variably defined) are found with increased frequency in women undergoing evaluation for infertility than in unaffected women; whether their presence contributes to in vitro fertilization failure remains unknown, as studies evaluating the link between aPL positivity and assisted reproductive technology (ART) outcome are heterogeneous and report mixed findings.57–60 Some studies suggest that RA is associated with decreased ovarian reserve and infertility, which may be related to disease activity.14,61–63 Research on fertility in the context of other RDs is more limited. Patients with SpA and systemic sclerosis do not seem to have decreased fertility,64–66 while very small studies suggest that patients with IIM may have decreased ovarian reserve.46,67 Adults with childhood-onset RDs may face infertility as a result of disease- and treatment-related factors.68,69 Larger, controlled studies are needed to confirm whether having an RD inherently increases the risk of infertility.

Disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) do not seem to impair fertility.70 However, use of both non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), which interfere with the rupture of the ovarian follicle, and high-dose systemic corticosteroids, which interfere with the hypothalamic-pituitary axis leading to menstrual irregularity, may delay conception.61 NSAID use should be avoided in patients who are having difficulty conceiving and whose disease can be adequately controlled without them.16 Patients who require high-dose systemic corticosteroids to control their disease should ideally defer pregnancy until the disease is quiescent. Intravenous monthly CYC is gonadotoxic, and cumulative exposure significantly increases the risk of POI and infertility; studies in patients with SLE have shown that the risk of POI is increased in older patients with SLE and those with longer disease duration.54 Treatment with gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists, given 10–14 days prior to the CYC dose, may reduce POI risk.54 Patients who require treatment with monthly CYC may also consider oocyte cryopreservation prior to treatment to preserve future fertility, but issues of timing and hormone stimulation may be prohibitive. Alternatively, the Euro-Lupus low-dose CYC regimen does not affect ovarian reserve as measured by anti-Müllerian hormone levels.71

For patients with RD who face infertility, ART, including in vitro fertilization, is an option that is generally considered safe when undertaken in the context of quiescent disease and adherence to RD-specific treatment recommendations: prophylactic heparin/low–molecular–weight heparin (LMWH) for those with aPL alone or obstetric APS, and continuation of therapeutic heparin/LMWH for those with thrombotic APS (Table 2).16 Ovarian stimulation for oocyte or embryo cryopreservation may be done even while the patient is on teratogenic medications (other than CYC) and may enable future pregnancy when fertility might otherwise be limited by age.

Table 2: Recommendations for the management of patients with systemic rheumatic disease undergoing assisted reproductive technology

|

Clinical scenario |

Proceed with ART? |

Treatment recommendations |

|

Active RD |

No |

Treat RD, defer ART |

|

Stable RD, aPL–negative |

Yes |

Continue pregnancy-compatible RD medications only for IVF with plans for immediate embryo transfer and attempting pregnancy; Continue all RD medications, except CYC, if planning embryo or oocyte cryopreservation |

|

aPL–positive, no APS |

Yes |

Prophylactic heparin or LMWH during ART (conditionally recommended, discuss with patient) |

|

Obstetric APS |

Yes |

Prophylactic heparin or LMWH during ART (strongly recommended) |

|

Thrombotic APS |

Yes |

Continue therapeutic heparin or LMWH (strongly recommended) |

aPL = antiphospholipid antibody;APS = antiphospholipid syndrome;ART = assisted reproductive technology;CYC = cyclophosphamide;IVF = in vitro fertilization;LMWH = low-molecular-weight heparin;RD = rheumatic disease.

Pregnancy

Maternal and foetal risk and outcomes

Systemic lupus erythematosus and antiphospholipid syndrome

The association between underlying RD and risk of APOs is best established in the context of SLE and APS. Nationwide data from the United States have shown a significantly greater decline in maternal mortality rates among women with SLE between 1998 and 2015 than among women without SLE during the same period.1 However, maternal mortality and risk of maternal and foetal complications – including preeclampsia, preterm birth, small for gestational age (SGA) neonates, spontaneous abortion and stillbirth – remain elevated.1,2,6 Among women with SLE, those with active or prior lupus nephritis are at increased risk of APOs, including preeclampsia and foetal loss.72 Prior lupus nephritis is both a risk factor for and can present similarly to preeclampsia.72 SLE is associated with a fourfold increased risk of haemolysis, elevated liver enzymes and low platelets (HELLP) syndrome,73 whose manifestations overlap with those of disease flare. For women with stable, quiescent SLE at the time of conception, severe disease activity during pregnancy is rare.74,75 Hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) use is recommended during pregnancy for all patients with SLE16,19 and is associated with decreased disease activity.76

In pregnant women with aPL positivity, with or without SLE, one prospective study from 2012 reported a tenfold increase in the risk of APOs.4 A 2022 international prospective cohort study of patients with aPL reported that 27% resulted in early pregnancy loss, and 23% of the pregnancies that continued resulted in an APO.3 APS is associated with an increased risk of preeclampsia, preterm birth, IUGR, spontaneous abortion and stillbirth.77–80 Prior thrombosis predicts aPL-associated pregnancy morbidity;3,4,81–84 however, prior pregnancy morbidity or loss alone may not.4,81,82 Guideline-concordant treatment with low-dose aspirin and anticoagulation is associated with improved live birth rates.85–87 In women with purely obstetric APS, thrombotic events can occur during pregnancy;85 there are no comparative studies to quantify this risk, and prophylactic anticoagulation likely offsets it to some extent. For those with thrombotic APS, thrombosis risk is high in the antenatal and postpartum periods.88 While it may be difficult to differentiate immune-mediated thrombocytopaenia from physiologic thrombocytopaenia in the later stages of pregnancy, first-trimester thrombocytopaenia in obstetric APS is an independent risk factor for preterm delivery.89 APL positivity and APS are also linked to the development of HELLP syndrome, explained in part by aPL-mediated endothelial dysfunction and thrombotic microangiopathy in these patients.90 Catastrophic APS, which can overlap with or be confused for HELLP syndrome, is a rare occurrence in pregnancy associated with high maternal mortality.91

Inflammatory arthritis

RA is associated with various adverse maternal and foetal outcomes, including an increased risk of C-section, preeclampsia, gestational hypertension, preterm delivery, SGA, neonatal intensive care unit admission, spontaneous abortion and foetal loss.92,93 Some of this risk is likely attributable to active disease and systemic corticosteroid use during pregnancy.94–96 Approximately half of the women with RA experience pregnancy-induced remission.97,98

PsA has been associated with an increased risk of gestational hypertension and SGA,9 and axial SpA has been associated with increased C-section rates.8,10 Women with PsA and SpA may experience disease activity during or after pregnancy, although this is generally mild.99,100 Use of tumour necrosis factor inhibitors (TNFis) during pregnancy in these groups has been associated with decreased disease activity,99 and discontinuation of TNFis upon conception has been associated with increased disease activity.101

With preconception counselling, close monitoring and management with pregnancy-compatible medications, the majority of women with inflammatory arthritis can maintain low levels of disease activity throughout pregnancy and achieve favourable pregnancy outcomes.8,102

Undifferentiated connective tissue disease

UCTD is the RD that is most likely to be newly diagnosed in pregnancy.103,104 Women with UCTD versus healthy comparators are also more likely to experience an APO; risk factors may include extractable nuclear antigen antibody and aPL positivity.105,106 Some studies suggest that up to 25% of patients with UCTD may experience disease flare during pregnancy, which, in rare cases, can be severe and lead to a diagnosis with well-defined connective tissue disease, such as SLE;107,108 risk factors for disease progression include having double-stranded DNA antibodies, active disease in early pregnancy109 and preeclampsia in a prior pregnancy.110

Other rheumatic diseases

Research on pregnancy outcomes in rare systemic autoimmune RDs has shown increased rates of various maternal and neonatal complications, depending on the specific diagnosis.11,15,111–116 A 2020 systematic literature review and meta-analysis found that systemic sclerosis may increase the risk of gestational hypertension, miscarriage, IUGR, low birth weight, C-section and preterm delivery; however, the data do not allow firm conclusions to be drawn regarding the relationship between pregnancy and disease worsening or improvement.111 A 2018 United States nationwide inpatient database study including 853 IIM delivery-associated hospitalizations reported an elevated risk of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy,115 and a 2020 Swedish nationwide register study reported increased C-section and preterm delivery rates and low birth weight in IIM.114 Small-vessel vasculitides are associated with late preterm delivery, increased risk of IUGR and disease flare during pregnancy; severe flares seem uncommon.117

Although rare, Takayasu’s vasculitis is unique among systemic vasculitides and deserves a special mention as it occurs most commonly in young women.118 Similarly to other RDs, active disease prior to and during pregnancy significantly increases the risk of maternal morbidity – most commonly new-onset or worsening hypertension – and various APOs.119 While women with Takayasu’s can have successful pregnancies,15,120 disease-related vascular damage may increase the risk of poor outcomes, even in the absence of active disease.121,122

In general, disease activity immediately preceding or during pregnancy is likely the most significant risk factor for APOs.74,105,119,123–126 Complicating both clinical management and research in this area, RD disease activity may present similarly to physiologic symptoms of pregnancy or obstetric complications, and, other than for SLE,127–129 pregnancy-specific disease activity measures are not available.

Pre-pregnancy Assessment and Management of Rheumatic Disease During Pregnancy

Impact of autoantibodies on pregnancy management

Autoantibodies that affect pregnancy monitoring parameters and therapeutic decisions are aPLs, anti-Sjögren’s syndrome A (Ro/SSA) and anti-Sjögren’s syndrome B (La/SSB). Among the aPLs, which include lupus anticoagulant, anticardiolipin and anti-beta–2–glycoprotein I antibodies, lupus anticoagulant poses the greatest risk for APOs in patients with and without SLE, with a relative risk of 12 (p=0.0006) as reported in the PROMISSE study.4 Regardless of the patient’s clinical phenotype, low-dose aspirin is recommended for preeclampsia prevention in women with SLE and/or aPL positivity.16 LMWH is added at prophylactic doses for women with prior obstetric APS, based on aPL positivity and prior APS criteria-defined pregnancy complications,30 and at therapeutic doses for women with thrombotic APS.16 Other articles provide a detailed discussion of the immune-mediated mechanisms driving placental dysfunction and related pregnancy complications associated with obstetric APS.130,131 Some studies suggest that HCQ may mitigate the risk of pregnancy complications in obstetric APS,132,133 and on–going research will determine whether additional immunomodulatory or immunosuppressive agents may have a role in this context.

Anti-Ro/SSA and anti-La/SSB antibodies are associated with risk of neonatal lupus erythematosus (NLE) (although isolated anti-La/SSB is uncommon, and its association with NLE is poorly characterized).134 NLE most commonly presents with transaminitis, rash and cytopenia; congenital heart block (CHB) occurs in 2% of anti-Ro/SSA pregnancies.135 HCQ appears to decrease the risk of CHB among women with a prior pregnancy complicated by this outcome.136 Given the relative safety of HCQ in pregnancy, it is recommended for all pregnant women with these antibodies regardless of the underlying RD, clinical manifestations, or disease activity.16

The ACR guideline conditionally supports serial foetal echocardiography from between 16 and 18 weeks through 26 weeks of gestation for all pregnant women with anti-Ro/SSA and/or anti-La/SSB antibodies.16 This recommendation contrasts both with the EULAR guideline, which supports foetal echocardiography only in the context of suspected foetal dysrhythmia or in women who have experienced CHB in a prior pregnancy19 and with a recent SMFM consensus statement that recommends against routine serial foetal echocardiography.36 The EULAR and SMFM recommendations are based on both potential foetal or maternal harm from fluorinated corticosteroid treatment and a lack of definitive data supporting the benefit of such treatment.137 The ACR guideline conditionally recommends short-term dexamethasone treatment for potentially reversible first or second-degree CHB or myocardial inflammation but not third-degree CHB;16 this recommendation is based on limited data suggesting potential benefit and the high risk of morbidity and mortality without treatment.138 A 2022 multicentre retrospective study proposed an anti-Ro/SSA antibody titre threshold, below which CHB risk is sufficiently low that routine surveillance with foetal echocardiography may not be warranted.139 On–going and future studies will help establish the best practices for the screening and prevention of this rare but devastating outcome.

Medication use during pregnancy

Management of RD during pregnancy is complicated by several factors: many medications are not well studied in the context of pregnancy; providers may not be familiar with the safety profiles of therapeutic options and how best to weigh the risks and benefits of use; and patients may be more hesitant to use medications during this time. ACR and EULAR guidelines summarize the evidence for commonly used RD medications and provide recommendations for use.16,140 Since the publication of these guidelines, which support the continuation of NSAIDs through the second trimester,16,140 the United States Food and Drug Administration has advised discontinuing NSAIDs after 20 weeks due to the risk of oligohydramnios.141 Given the link between cumulative corticosteroid exposure and premature delivery, treatment with systemic corticosteroids should be limited to the lowest dose and shortest duration needed to control disease activity, with the substitution of pregnancy-compatible steroid-sparing medications as appropriate.96 Steroid-sparing medications or DMARDs with strong recommendations for continued use during pregnancy include HCQ, sulfasalazine, colchicine, azathioprine and certolizumab.16 Continuation of cyclosporine and tacrolimus during pregnancy is conditionally recommended, with blood pressure monitoring.16 According to ACR, TNFis – other than certolizumab, which does not cross the placenta – are conditionally recommended for continuation through the first and second trimester, with discontinuation conditionally recommended in the third trimester due to concern for neonatal immunosuppression;16 EULAR supports consideration of both etanercept and certolizumab for use throughout pregnancy.140 The American Gastroenterological Association recommends continuing all TNFis in patients with inflammatory bowel disease through the third trimester, with some variation in the timing recommended for the final dose depending on the agent’s half-life.142 Given the limited safety data in patients with RD, ACR and EULAR recommend discontinuing other biologics (i.e. rituximab, anakinra, belimumab, abatacept, tocilizumab, secukinumab and ustekinumab) at conception.16 Due to reassuring data in the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease, the American Gastroenterological Association recommends continuing ustekinumab throughout the first and second trimesters.142 Continuation of these medications beyond conception may be appropriate in certain clinical contexts, but more data is needed to inform future updated guidelines.

Delivery and Postpartum Considerations

RD-specific issues relevant to the mode of delivery may include hip arthritis or prior total hip replacement and cervical spine disease. Otherwise, the mode of delivery is determined based on obstetric considerations. In terms of timing, early induction of labour may be recommended due to RD-associated pregnancy complications, such as hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, after weighing the maternal and foetal risks associated with continued pregnancy versus delivery.143

Postpartum considerations include monitoring and treatment for disease flare, resumption of maintenance therapies that may have been discontinued during pregnancy, management of thrombotic risk in women with aPL and counselling on breastfeeding. The risk of postpartum disease flare is particularly high for women with RA.98 Women with SLE are more likely to experience disease flare postpartum than outside of pregnancy,144 but rates of postpartum flare are comparable to those during pregnancy and are low overall in women with quiescent disease.75

There is a well–established increased risk of thrombosis in the postpartum period in the general population, to a greater degree than that seen during pregnancy.145 For women with obstetric APS, the ACR guideline recommends prophylactic anticoagulation for 6 to 12 weeks postpartum;16 the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology recommends postpartum prophylaxis in women with aPL (not specifically defined) who have additional risk factors for thrombosis.146

Women with RD and rheumatologists may have concerns about medication use while breastfeeding.147,148 Some medications commonly used to treat RD are not safe to continue while breastfeeding, such as methotrexate, leflunomide, mycophenolate, CYC and thalidomide.16 The ACR guideline endorses the use of biologic DMARDs while breastfeeding; given the limited clinical safety data, EULAR is more conservative but supports the continuation of these agents in the absence of available alternatives.16,140 Women with RD should be counselled about the benefits of breastfeeding, particularly in the first 6 months postpartum, in accordance with the recommendations of the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology149 and the American Academy of Pediatrics.150 LactMed® (Drugs and Lactation Database) is an accessible, evidence-based resource that provides comprehensive information about medication use and breastfeeding.151

Conclusions

Many RDs are diagnosed before or during a woman’s childbearing years; as a result, rheumatologists should be familiar with the risks that patients with RD encounter in relation to family planning and pregnancy. For individuals of reproductive age with RD who do not desire pregnancy, effective contraception is critical and underused. Rheumatologists should counsel these patients on the use of safe and effective contraception and, in some cases, may need to educate other specialists about the safety considerations of various contraceptive methods in high-risk patients with RD.

Patients with RD who are planning for pregnancy should have preconception assessment and counselling regarding autoantibody profile, disease manifestations and medications. For those who face infertility or need to delay pregnancy, ART should be recommended when available and appropriate; treatments may be individually tailored to mitigate associated risks. During pregnancy, close monitoring and collaborative multidisciplinary management can often lead to favourable maternal and foetal outcomes. Many studies demonstrate that active disease before and during pregnancy confers an increased risk of maternal morbidity and APOs; for women with RD, regardless of the specific diagnosis, entering pregnancy with quiescent disease while on pregnancy-compatible medications is key. For some patients with RD, the postpartum period may be a vulnerable time due to the risk of disease exacerbation, concerns about breastfeeding and new challenges that may emerge as they manage their own health while caring for a newborn.

Reproductive health is a central aspect of overall health and wellbeing for many women. Rheumatologists should anticipate the challenges that may arise for women with RD during their reproductive years, discuss these challenges with their patients, and incorporate evidence-based practices into their care in order to optimize the reproductive health of every patient.