Advances continue to be made in the treatment of systemic sclerosis (SSc, also termed ‘scleroderma’); however, it remains a challenging disease for both patients and for the clinicians caring for them. The purpose of this review is to highlight these advances, as opposed to going into detail of the many different aspects of treatment of this multisystem disease. SSc is different from other connective tissue diseases in that its clinical manifestations result mainly from vascular abnormality and fibrosis rather than from inflammation, although patients with overlap syndromes have inflammatory features, as do patients with early diffuse cutaneous SSc (dcSSc). This has major implications for management.

After ‘setting the scene’ with a brief background covering disease subtyping and autoantibodies, this review describes the broad principles of management of SSc and then focuses on certain aspects of the disease where there have been recent advances. These aspects are digital vasculopathy (Raynaud’s phenomenon [RP] and digital ulceration), pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH), interstitial lung disease (ILD) and early dcSSc disease. Treatment of intestinal failure and calcinosis will be discussed briefly. Finally, some future challenges in developing and delivering new treatments are highlighted.

The spectrum of systemic sclerosis: Disease subtyping and autoantibodies

Disease subtypes

There are two main subtypes of SSc: limited cutaneous SSc (lcSSc), the more common subtype, and dcSSc.1,2 These subtypes are defined purely on the basis of the extent of the skin involvement; in lcSSc, this is confined to distal to the elbows and knees, and face and neck, whereas in dcSSc the proximal limb and/or trunk are involved. The two different subtypes have very different disease trajectories and different autoantibody associations, and although there are many common elements to management, treatment of early dcSSc (discussed below) is very different from that of early lcSSc. It is important to diagnose patients with dcSSc early because they are at high risk of early internal organ involvement, which can be life threatening. In patients with dcSSc, skin tightening of the extremities often progresses proximally very rapidly, and in the early inflammatory phase patients may be misdiagnosed as having rheumatoid arthritis because of their presentation with finger pain and swelling, which often occurs at the same time as (or precedes) the onset of RP. This is in contrast to patients with lcSSc who tend to have had RP for many years prior to diagnosis. As a very broad generalization, lcSSc tends to be associated with a more vascular phenotype than dcSSc, whereas patients with dcSSc tend to have more fibrotic disease (widespread skin thickening and a higher prevalence of early pulmonary fibrosis), although scleroderma renal crisis (one of the vascular manifestations of SSc) is much more common in dcSSc than in lcSSc.

Autoantibodies

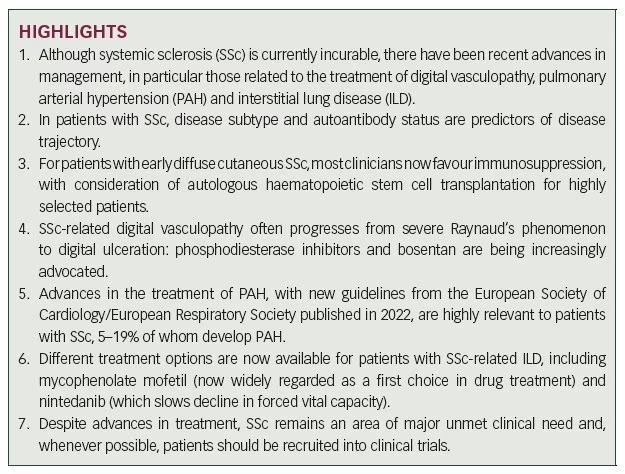

There are several SSc-specific autoantibodies. Table 1 lists the most clinically relevant; more comprehensive listings can be found elsewhere.3,4 The different autoantibodies tend to associate with different phenotypes (Table 1).3–7

Improved prediction of disease course, informed by autoantibody status in addition to disease subtype, has been one of the major advances in management and a first step towards a stratified medicine approach. For example, autoantibody status has been shown to predict survival and cumulative incidence of pulmonary fibrosis, and (as examples of both of these) in a large single-centre study,8 patients who were anticentromere antibody positive had the highest survival and lowest incidence of pulmonary fibrosis, whereas patients who were anti-topoisomerase 1

(anti-Scl-70) positive had the highest incidence of pulmonary fibrosis.

General principles of management

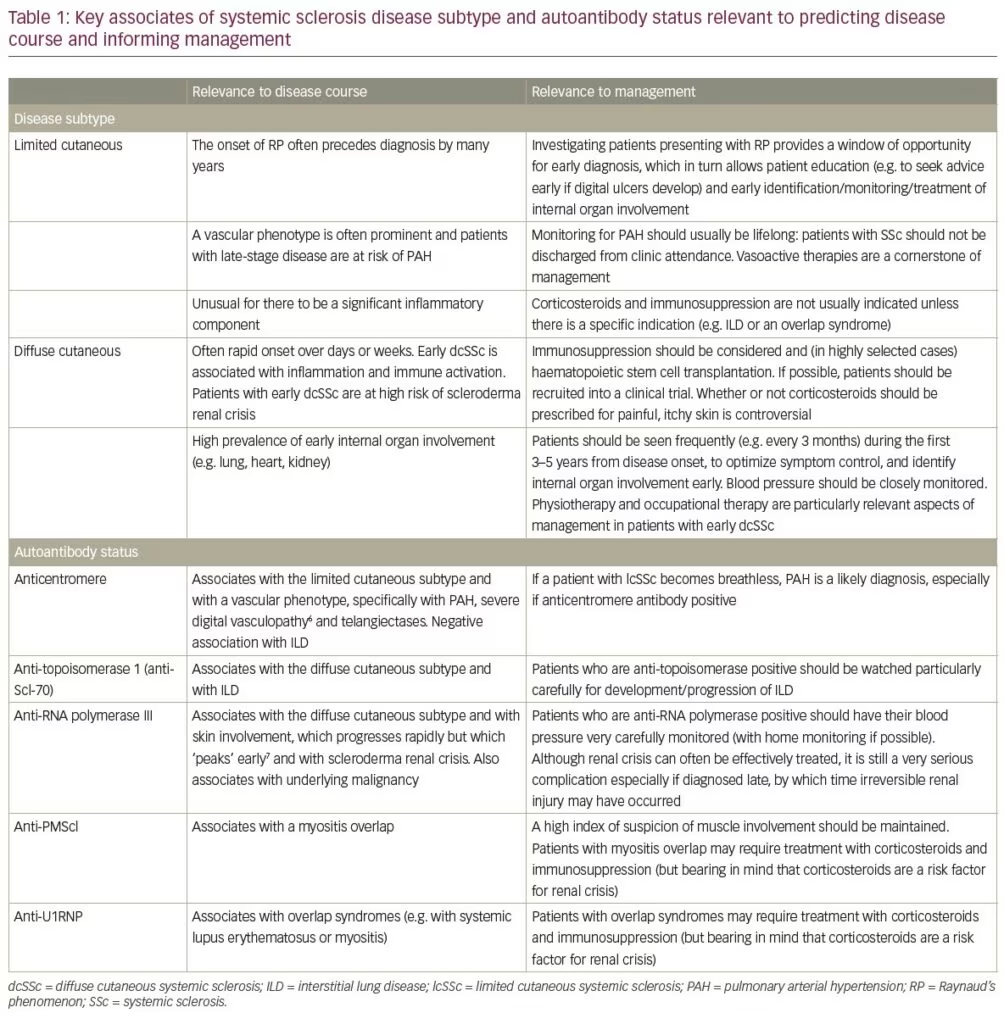

A detailed description of management is outside the scope of this review but can be found elsewhere.9–12 Certain broad principles apply (Figure 1). Early diagnosis is key to allowing early identification, monitoring and treatment of different ‘complications’ of SSc before irreversible tissue injury has occurred or progressed. Patient education is a cornerstone of management as for any chronic disease, and because SSc has a major impact on function, most patients are likely to benefit from physiotherapy and occupational therapy input. A motivated multidisciplinary team is essential to delivering high-quality care, which should include pain management because it is increasingly recognized that most patients with SSc experience pain, which can occur for a variety of reasons.13

A key question is whether there is a treatment that can modify the underlying disease. This will be discussed further under ‘early dcSSc’, although the question is pertinent also in patients with lcSSc because it is possible that vascular remodelling agents could modify vascular disease progression,14 although currently there is no good evidence base to support this.

Although there is currently no cure for SSc, there have been advances in treatment of the individual organ-based features of disease and of the associated digital vasculopathy, discussed in the next sections. The UK Scleroderma Study Group has published consensus best practice guidelines for digital vasculopathy and some organ-based ‘complications’.15–17 As SSc is a multisystem disease, many different medical and surgical specialists may be involved in delivering care.

Digital vasculopathy

Context

Almost all patients with SSc experience RP, which is the most common presenting feature and can be very severe with a major impact on quality of life.18 Approximately 50% of patients progress to painful digital ulcers,19 and a minority to gangrene.20 The reason why RP is so severe, frequently progressing to irreversible tissue injury, is because SSc-related digital vasculopathy is associated with structural as well as functional change, in contrast to the situation in patients with primary RP, in whom vasospasm is a purely functional abnormality and completely reversible.21

Advances in management

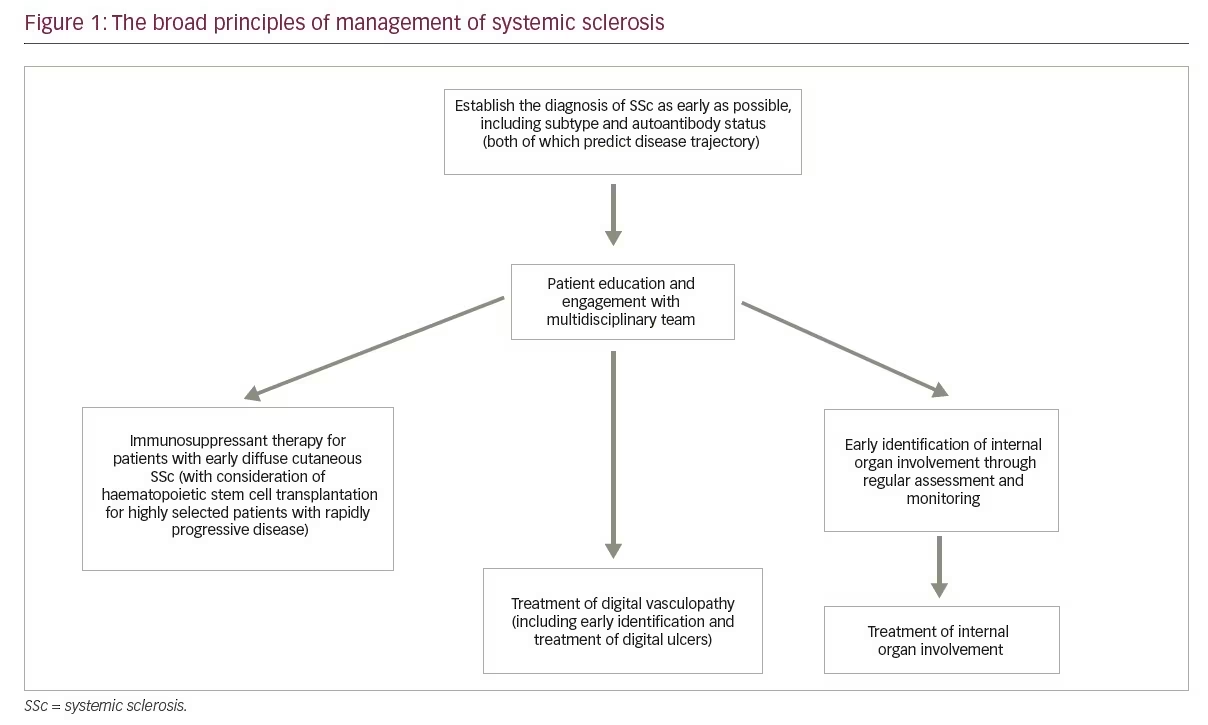

Recent advances in the treatment of SSc-related digital vasculopathy parallel those of PAH because both conditions share common elements of pathophysiology. In both conditions, drug treatments are aimed at blocking the endothelin pathway, or supplementing either the nitric oxide pathway or the prostacyclin pathway.22 Figure 2 summarizes current approaches to treatment,23 which include ‘general/lifestyle’ measures and non-pharmacological treatments,24 as well as specialist nursing care for patients with digital ulcers.25 Recent advances are as follows.

The increased use of phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors for both Raynaud’s phenomenon and for digital ulceration

Phosphodiesterase type 5 (PDE5) inhibitors supplement the nitric oxide pathway by inhibiting degradation of cyclic guanosine monophosphate. Meta-analyses have suggested benefit in SSc-related RP26,27 and most clinicians would now recommend PDE5 inhibitors as second line after calcium channel blockers, with which they can be used in combination.28 Although PDE5 inhibitors have been less studied for the treatment of digital ulcers than for RP, it is likely that they confer some benefit. The SEDUCE study (comparing sildenafil with placebo)29 failed to meet its primary endpoint, which was time to ulcer healing, but did suggest some beneficial effect of sildenafil. PDE5 inhibitors are recommended in the NHS England pathway for treatment of SSc-related digital ulcers, being positioned after standard medical treatment (primarily a calcium channel blocker) but before bosentan.30

The increased use of bosentan for digital ulcers

Bosentan is an endothelin-1 receptor antagonist. Two placebo-controlled trials (RAPIDS-131 and RAPIDS-232) both suggested benefit from bosentan in prevention of new digital ulcers (although no effect on ulcer healing). However, the DUAL-1 and DUAL-2 studies of macitentan,33 another dual endothelin receptor antagonist, showed no effect. Bosentan is licensed in the UK for prevention of recurrent SSc-related digital ulcers. Now that bosentan is out of patent, its use is likely to continue to increase. The NHS England pathway positions use of bosentan after a PDE5 inhibitor but before intravenous (IV) prostanoid therapy.30

The ‘positioning’ of intravenous prostanoid therapy

IV administration of iloprost, a prostacyclin analogue, promotes healing of digital ulcers and is also used to treat severe RP.34 However, the treatment requires hospitalization, and is frequently associated with systemic adverse effects. Especially during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, when there was a reluctance to admit patients to hospital, increased reliance was placed on prompt ulcer recognition and maximizing oral vasodilator therapy (including with a PDE5 inhibitor), often combined with bosentan. Practice varies between countries, but it is likely that with increasing use of PDE5 inhibitors and bosentan, IV prostanoids may in the future be less used than previously, although they will continue to be used for acute digital ischaemia and refractory digital ulcers. Several recent papers have examined different treatment schedules because there is considerable variation across centres in IV prostanoid regimens and no consensus opinion.35,36 Many clinicians use the 5-day regimen described by Wigley et al.,37 although others favour a single monthly infusion,35 and longer durations of treatment have also been proposed.36 Disappointingly, a placebo-controlled trial of treprostinil, an oral prostacyclin analogue,38 failed to meet its primary endpoint (change in net digital ulcer burden) although some benefit was reported, with further evidence in favour coming from a retrospective analysis of data from 51 patients discontinuing treprostinil after the open-label extension.39 In summary, IV prostanoids are probably administered less frequently than they were pre-pandemic, but they remain an important part of the therapeutic armamentarium especially for acute/critical ischaemia. Developing new routes of prostanoid administration, and optimizing protocols for IV infusion, continue to attract interest.

Other advances

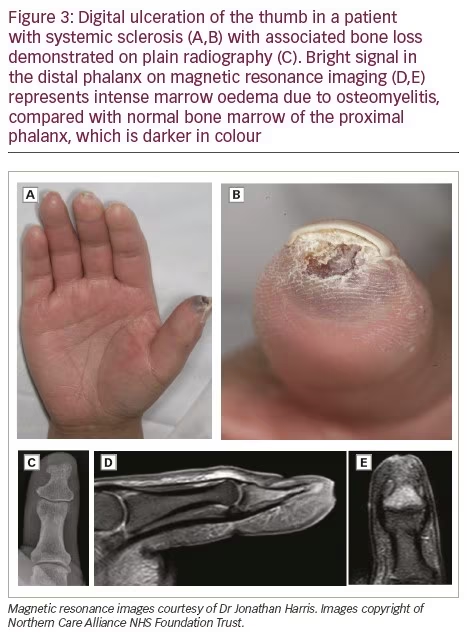

Early diagnosis of osteomyelitis with magnetic resonance scanning, allowing prompt treatment

Many digital ulcers are infected,40 sometimes with underlying bone infection. Magnetic resonance imaging allows early diagnosis of bone infection, which can be difficult to recognize on plain radiographs either because plain radiographs do not demonstrate early bone infection or because if change is demonstrated on plain radiographs (especially at the fingertip), it can be difficult to decide whether this change is due to SSc-related acro-osteolysis or to bone infection (Figure 3). Prolonged antibiotic therapy for osteomyelitis can save a digit.

Procedural treatments for digital ulceration

Botulinum toxin injections have been advocated for severe digital ischaemia in patients with SSc, especially those with digital ulcers, on the basis of multiple anecdotal reports/small series, with experience summarized in several recent reviews.41–45 However, a placebo-controlled clinical trial in 40 patients with SSc did not demonstrate definite benefit in patients with SSc-related RP (although there was some improvement in secondary outcome measures),46 and a more recent placebo-controlled trial in 90 patients also failed to demonstrate benefit.47 Digital (palmar) sympathectomy has attracted considerable interest in recent years,48,49 again with multiple anecdotal reports and small series. It should only be performed by an experienced surgeon. Autologous fat grafting has also been advocated.50 Controlled trials of procedural treatments are challenging.51 The need for further research into digital ulcer debridement, which can be achieved using different methods, has recently been highlighted.52

In conclusion, although there have been recent advances, considerable challenges remain, with a recent systematic review concluding that only calcium channel blockers and PDE5 inhibitors are more effective than placebo for secondary RP,27 and that even for these, treatment effect is below the minimally important difference. Effective treatments for digital vasculopathy are therefore badly needed.

Pulmonary arterial hypertension

Context

PAH and ILD are now the main causes of death in patients with SSc.53 In patients with SSc, pulmonary hypertension is most commonly either due to PAH (WHO Group 1), or secondary to pulmonary fibrosis (WHO Group 3),54 although combinations of the two frequently exist55 and there can be other reasons (e.g. secondary to left heart disease [WHO Group 2]). This section deals with PAH, which is a disease of the pulmonary arteries and part of the spectrum of vascular abnormality that characterizes SSc. Approximately 5–19% of patients with SSc develop PAH,54 including patients with well-established lcSSc, and so a high index of suspicion should be maintained. Clinicians should be aware of the patient with severe digital ischaemia and multiple telangiectasias (often with a positive anticentromere antibody), reflecting a vascular phenotype at particularly high risk of PAH. Advances in PAH management have driven advances in SSc care more generally, because it is now recognized that patients should be monitored for life, and that ‘stable’ disease after (say) 10–15 years of disease duration does not pre-empt development of PAH. The mortality of SSc-related PAH is higher than that due to idiopathic PAH.56

Advances in management

One of the main advances has been early detection, with the setting up of screening programmes for patients with SSc. Early detection and treatment is associated with improved survival.57 There are different screening guidelines/algorithms, for example the European Society of Cardiology (ESC)/European Respiratory Society (ERS) guidelines,54 and the DETECT and the Australian Scleroderma Interest Group algorithms.58,59 PAH should always be considered if a patient complains of breathlessness (although this may be a late symptom in patients with SSc who often have mobility issues and therefore a reduced exercise tolerance for other reasons), if there is an accentuated pulmonary component to the second heart sound, if there is a disproportionate fall in diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide compared with forced vital capacity (FVC) on pulmonary function testing, or if there are concerning features on echocardiography. The last 20 years have seen a very large number of clinical trials investigating new treatments and combination treatments for PAH.54,60 It is outside the scope of this review to discuss these, but some general points are as follows.

- Clinical practice will differ between countries, but the treatment of PAH is a highly specialized field. In the UK, for example, there is a national network of pulmonary vascular disease centres, to which patients should be referred if PAH is suspected or diagnosed.

- Drug treatments for PAH act mainly by antagonizing the endothelin pathway, or supplementing the nitric oxide or prostacyclin pathways, with drugs including:

– antagonizing endothelin-1 with endothelin receptor antagonists (bosentan, ambrisentan, macitentan)

– supplementing the nitric oxide pathway with PDE5 inhibitors (sildenafil, tadalafil) or a guanylate cyclase stimulator (riociguat)

– supplementing the prostacylin pathway with IV, subcutaneous or inhaled prostanoid therapy or with selexipag (a prostacyclin receptor agonist).

These drugs are often used in combination, for example dual therapy with a PDE5 inhibitor and endothelin receptor antagonist, or triple therapy with addition of a prostacylin analogue. The updated ESC/ERS guidelines54 provide a very comprehensive set of recommendations.

- In patients deteriorating despite optimal/maximal drug therapy, lung transplantation may be considered.54

- Although treatment and survival have improved, PAH continues to be associated with high morbidity and mortality.60–62

Interstitial lung disease

Context

ILD tends to occur earlier in the disease course than PAH, especially in patients with dcSSc, and is also associated with high morbidity and mortality. A minor degree of ‘stable’ ILD is very common, but a proportion of patients will have progressive change that can be life threatening.63 As stated earlier, patients who are anti-topoisomerase positive are at especially high risk.8,64 It is important to diagnose ILD early, so that treatment can be commenced without delay,65 hence (as with PAH) the rationale for regular screening, with history, examination (listening for late inspiratory crackles) and pulmonary function testing (looking for a restrictive defect and for a fall in the FVC and/or diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide from when last tested). Best practice is for all patients with SSc to have a baseline high-resolution computed tomography scan,66 which should be repeated if there is clinical concern that ILD might have newly developed or progressed.

Advances in management

Although SSc-related ILD continues to be associated with a high mortality, over the past 15 years there have been advances in treatment that can slow progression.66 Recent review articles on SSc-related ILD provide more detail,67–70 but key findings relevant to changing clinical practice are summarized here. Two randomized placebo-controlled trials reported in 2006 suggested benefit from cyclophosphamide.71,72 The Scleroderma Lung Study 1 compared 12 months’ oral cyclophosphamide with placebo and demonstrated modest benefit in FVC.71 This benefit in terms of FVC was confirmed in a smaller study in 45 patients comparing 6 months’ IV cyclophosphamide followed by azathioprine (plus low-dose prednisolone) with placebo, although the improvement in this smaller study was not statistically significant.72 The Scleroderma Lung Study 2, published in 2016,73 suggested that mycophenolate mofetil (MMF), administered for 24 months, conferred a similar benefit to oral cyclophosphamide administered for 12 months, as a result of which most clinicians then favoured MMF as first line because of a preferable safety profile of MMF compared with cyclophosphamide. More recently, nintedanib has been shown to slow decline in FVC, and this effect adds to that of MMF;74 there is therefore a rationale for these two drugs to be used in combination. Most clinicians would currently recommend MMF as first line (unless there was a contraindication to immunosuppression, for example recurrent infected finger ulcers), adding in nintedanib if the ILD progresses and adjusting the dose of nintedanib as necessary to minimize adverse effects.75 Nintedanib received European Commission approval for SSc-related ILD in April 2000 and was approved by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence in November 2021.

Other drugs have also recently been shown to confer benefit or to stabilize disease. These include subcutaneous tocilizumab (approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for SSc-related ILD in March 2021),76–79 and rituximab, which was shown to stabilize disease and to be of comparable efficacy to cyclophosphamide in the recently reported RECITAL trial.80,81 The next 2–3 years are likely to see new guidelines for SSc-related lung disease. It is probable that the choice of agent will differ between patients depending on whether or not they have other clinical features influencing the decision, for example tocilizumab or rituximab for patients with concomitant inflammatory arthritis.

Corticosteroids are not usually prescribed in patients with SSc-related ILD, unless there is thought to be a specific indication for these.

Despite these advances, better, more effective treatments are still required and so there is an ongoing need for clinical trials of targeted therapies. For patients with severe disease, lung transplantation should be considered, bearing in mind that in patients with SSc, gastrointestinal involvement and other features of disease may influence decisions about candidacy.82

Early diffuse cutaneous systemic sclerosis

Context

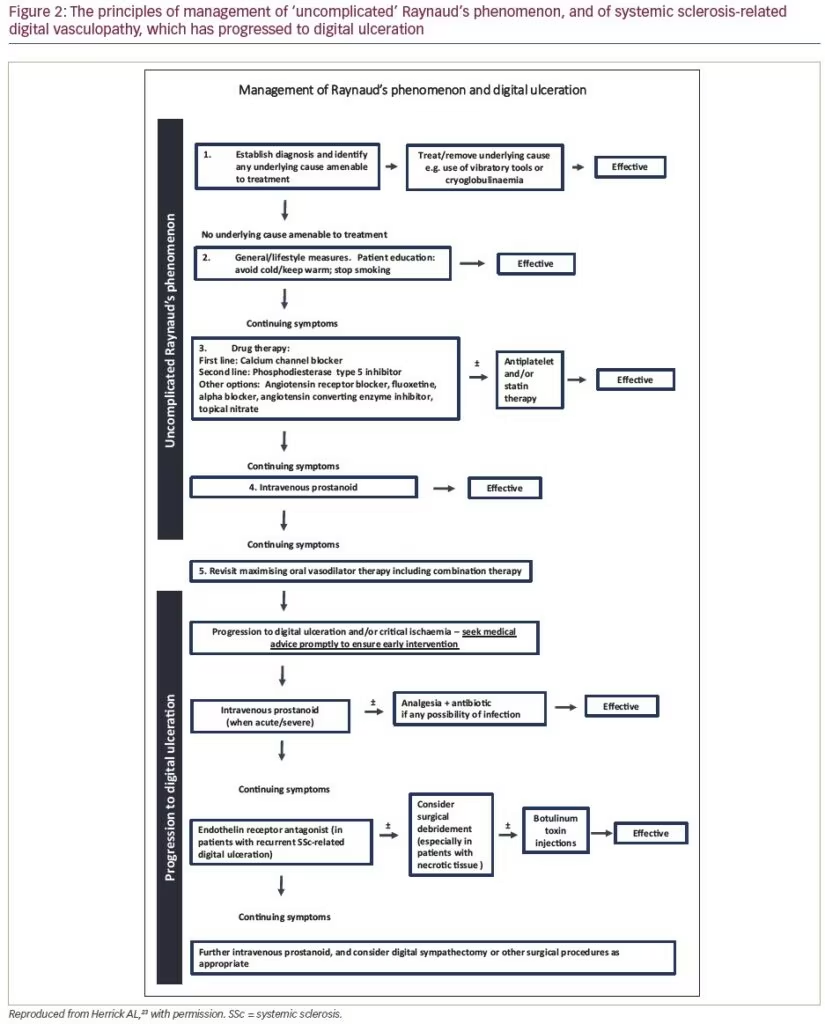

Early dcSSc is painful, disabling and associated with a high mortality. The high mortality is due to a high incidence of early internal organ involvement,83 whereas most of the pain and impact on quality of life is due to skin and musculoskeletal involvement.84 It is well recognized that the higher the modified Rodnan skin score (i.e. the more extensive the skin involvement), the higher the mortality,85–87 because the degree of skin involvement (scleroderma, meaning ‘hard skin’) is an index of disease severity in early dcSSc disease. Recent studies have benchmarked how the degree of skin involvement also associates with the degree of pain and disability,88,89 with a major impact on hand function (many patients have severe finger flexion contractures, which predispose to overlying ulcers) (Figure 4). Skin disease tends to ‘peak’ and then soften within the first 3–5 years, after which patients often stabilize.90 Patients should be closely monitored for these first 5 years.

Advances in management

A key point is that because of the rarity and potential severity of early dcSSc, and the need to identify effective treatment strategies (through clinical trials), patients should be referred to a specialist SSc centre.

Immunosuppression

There is no known disease-modifying agent for early dcSSc. Immune activation occurs early on in dcSSc, and the British Society for Rheumatology (BSR)9 and European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR)10 guidelines recommend immunosuppression. The EULAR recommendations suggest methotrexate on the basis of two randomized controlled trials, whereas the BSR guidelines suggest that methotrexate, MMF and cyclophosphamide are all reasonable choices. The European Scleroderma Observational Study (ESOS), which used an observational approach to compare methotrexate, MMF and cyclophosphamide and no immunosuppressant treatment,91 concluded that immunosuppression conferred modest benefit. Evidence from other sources, including analysis of skin scores in Scleroderma Lung Studies 1 and 292 and case series, lends further weight to immunosuppression despite the lack of high-quality clinical trial evidence.

Autologous haematopoietic stem cell transplantation

Three trials of stem cell transplantation suggested a benefit in terms of survival and also in skin score.93–95 This treatment should be considered in patients with rapidly progressive dcSSc and is now being used more widely, but only in highly selected patients. Patient selection is important because of the high risks of the procedure, although this is much safer with current protocols and with careful patient selection. In the Scleroderma: Cyclophosphamide or Transplantation (SCOT) study,95 treatment-related mortality was 3% at 54 months compared with a procedure-related mortality of 17% in a 2001 phase I/II trial.96 The efficacy of stem cell transplantation provides further rationale for immunosuppression in patients with early dcSSc.

Should corticosteroids be prescribed?

This is contentious. Corticosteroids could help many of the symptoms of early dcSSc (e.g. painful, itchy skin with stiffness) because these symptoms have an inflammatory basis, but corticosteroids are a risk factor for renal crisis.97–99 Patients with early dcSSc are already at risk of renal crisis and this risk is highest in those with rapidly progressive skin involvement and who are anti-RNA III polymerase positive100,101 (i.e. paradoxically, those patients who might be expected to benefit most in terms of symptomatic improvement from corticosteroids). The Prednisolone in early diffuse SSc (PRedSS) study, a controlled trial comparing moderate-dose prednisolone with placebo,102 was terminated early due to the COVID-19 pandemic and so was underpowered. None of the 35 patients recruited experienced a renal crisis and there was a weak signal favouring prednisolone.103 Further trials are required to address this important question.

Symptomatic treatment

This should never be forgotten. The pain from early dcSSc is severe, and so adequate analgesia is required and referral to a pain clinic should be considered. Physiotherapy (including hydrotherapy) and occupational therapy are important aspects of management.

Looking for underlying malignancy

Anti-RNA polymerase III antibody is associated with malignancy,104 and so an important part of management is to screen for malignancy in this clinical context.

Future therapies

The majority of recent and ongoing randomized controlled trials in patients with SSc are in patients with early dcSSc, and have included trials of a wide variety of targeted therapies. Discussion of these is outside the scope of this review, but can be found elsewhere.12,105 Randomized controlled trials are challenging due to the rarity of early dcSSc and the problems inherent in current outcome measures; for example, the modified Rodnan skin score106 (often the primary outcome measure) has a large interobserver variability.107 Whenever possible, patients with dcSSc should be recruited into one of the ongoing clinical trials because only in this way will effective treatments be identified.

Other advances

Although the key advances have been in the management of digital vasculopathy, PAH, ILD and early dcSSc, two other points to highlight are as follows.

- Nutrition. Nutritional issues are insufficiently recognized and intestinal failure as a cause of SSc disease-related mortality is sometimes overlooked.108 Total parenteral nutrition can be life saving. The dietician is an important member of the SSc multidisciplinary team.

- Calcinosis. There are no medical treatments of proven efficacy and the mainstays of current treatment are early antibiotic therapy when lesions become infected and (in selected cases) surgical debulking. The reason calcinosis has been included under ‘advances’ is that the past 10 years have at least seen recognition of calcinosis as an area of major unmet clinical need.109

Future challenges

As discussed, there have been significant advances in management, and a first challenge is to ensure that all patients are diagnosed and monitored appropriately, and that best practice guidelines are followed. A second challenge is to continue the quest to develop more effective treatment strategies for digital vasculopathy and the different forms of internal organ involvement, and also for disease modification. Drugs to modify the underlying disease are required not only for patients with early dcSSc but also for patients with lcSSc, the hypothesis being that vascular remodelling therapies, commenced early in the disease course, might slow progression (or even reverse) structural vascular disease.

Conclusions

Treatment of SSc depends on disease subtype, ‘stage’ and severity. The treatment of early dcSSc is very different from the treatment of a patient with established lcSSc. Best practice management depends on early diagnosis (first of SSc, second [in the patient with known SSc] of internal organ involvement or of digital ulceration) and monitoring, so that treatment can be initiated without delay. As SSc is a multisystem disease, management often involves input from different medical and surgical specialities, and also from the multidisciplinary team, with an emphasis on patient education. Although there have been recent advances in the treatment of digital vasculopathy, PAH, ILD and early dcSSc, treatment remains far from ideal and, where at all possible, patients should be recruited into clinical trials. ❑