Living with inflammatory arthritis (IA) can pose multiple challenges throughout the lives of patients, as well as to their families and friends. Despite major advances in available treatments for inflammatory arthritides, such as rheumatoid arthritis and spondyloarthritis, there remains an important role for the person living with IA. In this regard, an important aspect of care, alongside pharmacological treatment, is for patients to be able to self-manage their IA. Self-management refers to the patient’s ability to understand the disease and deal with the practical, physical and psychological impacts that come along with it.2 Therefore, self-management is useful to support an individual to achieve and maintain independence.

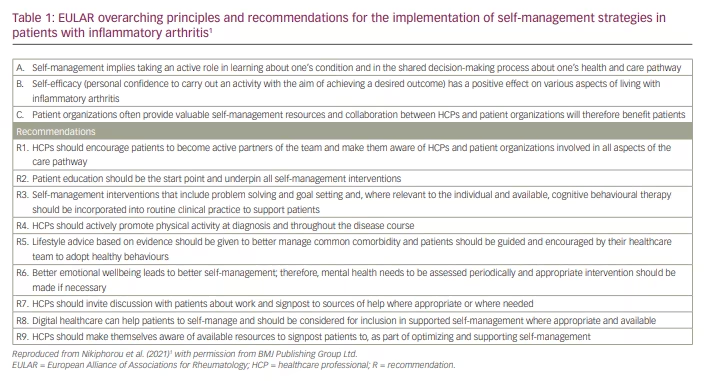

Self-management interventions in IA include problem solving, goal setting and cognitive behavioural therapy, all identified as crucial aspects of self-management and highlighted in the recent European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology (EULAR) recommendations on the implementation of self-management in IA (Table 1).1 These recommendations should guide supported patient self-management, alongside medical treatment. Patient education, one of the most studied interventions in randomized clinical trials, is an important component of

self-management.3 The EULAR recommendations highlight the need for patient education to be the starting point and to underpin all self-management interventions (recommendation 2), recognizing its value in improving treatment adherence, among other benefits.

Patient education can also play an important role in lifestyle changes that can improve disease symptoms and outcomes. Lifestyle factors, such as smoking, diet and exercise, tend to be poorly addressed in routine clinical care. Yet, their impact on disease course, treatment and outcomes is high.1 A similar issue is seen with physical and, especially, mental health comorbidities. Again, the latter remain poorly addressed, despite ample evidence suggesting their potential negative effects on disease outcomes.4

For self-management to be effective, it is imperative that healthcare professionals (HCPs) should be given appropriate training and guidance on how to support patients to self-manage. This is so that they can better engage in clinical self-management support and patient-centredness, as well as to improve their overall confidence to support self-management. The effectiveness and overall impact of self-management interventions is largely dependent on their inclusion in standard healthcare. Such interventions go beyond the ‘traditional’, drug-focused management of disease and its symptoms, and actively explore and address the disease impact on the patient’s priorities and quality of life.

The EULAR recommendations target HCPs and provide guidance on supporting people with IA to self-manage. They highlight the need for HCPs to familiarize themselves with available resources, so that they can better signpost patients to supported self-management.1 For example, several physical activity programmes and other community programmes exist, which can be beneficial in supporting patients in their care.5 Connecting people to community groups can support them in their care physically and emotionally. Social prescribing can have great benefits to the individual and society as a whole, helping to strengthen community bonds and improve individual and wider-community resilience, while also reducing health inequalities.6 For social prescribing and community signposting to work well, HCPs need to be aware of available resources, and appropriately inform and guide patients. Related to this, it has been strongly emphasized that being honest, building trust and establishing open communication between patients and HCPs can facilitate communication and optimal care overall.7–10 In this line, understanding individual circumstances and social context can help better support self-management.11,12

Naturally, by supporting patients to self-manage, they can become more confident and empowered to manage their disease. This way, they can become more proactive and involved in their care, and become better engaged with their healthcare team and with shaping their care pathway according to their needs. Self-management interventions implicitly focus on helping people in their everyday lives, acknowledging the potential impact of the disease on their daily routine. The focus is on supporting them to manage their symptoms through non-pharmacological interventions, enabling them to remain engaged at home, at work and in other social activities, and maintaining their independence.13 Self-management therefore plays a central role in the shared decision-making process, and this is a key overarching principle in managing IA and should be firmly integrated within routine rheumatology care.1

Another key principle of the EULAR recommendations is self-efficacy, which is defined as the confidence of an individual to carry out an activity that aims to achieve a specific goal/outcome and has beneficial effects in people living with IA.14 Furthermore, the role of patient organizations in supporting self-management has been strongly emphasized, taking a firm place as one of the three overarching principles in the recent EULAR recommendations.1

With increasing recognition of the value of self-management, several research-related activities are currently underway in the UK and other countries, with a focus on measuring the impact of specific self-management interventions. This drives from the identified need to prove the effectiveness of certain self-management interventions in IA, including, for example, the impact on disease activity.1 Additionally, there is a need to understand the cost-effectiveness of self-management interventions, including dedicated programmes to support patients in self-management. Dissemination and implementation strategies are currently underway to enhance the uptake of the EULAR recommendations.

In conclusion, supported self-management in IA represents a crucial component of overall disease management. HCPs should be informed about and given appropriate training on self-management strategies and available resources so that they can optimally support patients.Adherence to self-management recommendations can improve care and outcomes in people with IA, and can encourage a more proactive patient role in managing disease.